tl;dr: this is a series of posts about embedded firmware hacking and reverse engineering of a IoT device, a TomTom Runner GPS Smartwatch. Slidedecks of this work will be available here when I complete this series.

While specialization is key in most areas, I feel that in the field of information security too much specialization leads to tunnel vision and a lack of perspective. This blog is my attempt to familiarize myself in areas where I’m usually not comfortable with.

This series of posts will focus on a subject that I really sucked at until the last couple of months: reverse engineering of embedded systems.

01. Introduction

I will show you how I hacked a TomTom Runner GPS Smartwatch, by:

- Finding a memory corruption vulnerability exploitable via USB and possibly bluetooth (if paired);

- Taking advantage of said vulnerability to gain access to its encrypted firmware;

- Doing all this without ever laying a screwdriver near the device (no physical tampering).

After reading about the epic hacking of the Chrysler Jeep by Charlie Miller and Chris Valasek, and getting to watch their talk at Defcon this year (seriously, go watch it if you haven’t already), I felt really jealous because I wanted to be able to do that, so I got to work.

02. Motivations

Apart from the “hacker tingles” you get from hacking devices that exist in the real world, as opposed to hacking an abstract computer software / web application, there were some other reasons that got me into IoT hacking and motivated me to start reverse engineering such a device:

- Simpler architectures: Usually embedded devices have much less complex hardware and software than a general purpose computer or a smartphone/tablet with a complex OS;

- Fewer attack mitigations: These things usually lack memory protections such as ASLR, DEP, stack canaries, etc.;

- ARM Architecture: I had some previous experience in x86/x64 reversing, but having to get back to it, I feel that learning ARM is probably more important now than Intel architectures, well because Android, iOS, smartphones & tablets;

- Charlie Miller and Chris Valasek made it look easy :)

Then there’s the obvious buzzword of the year, The Internet of Things. Buzz aside, I feel that we’re really getting to the point where every electronic device is generating data and sharing it to the world.

We’re converging to a hyper-connected world, in the likes of a movie that really made an impression on me while growing up: Ghost in The Shell. The characters in the movie are so much surrounded (and implanted) with technology that they don’t even need to move their lips to talk – their thoughts are wirelessly transmitted to each other. We’re getting closer to that fascinating (and scary) future.

03. Research

So I looked around my house for devices I could start hacking. Found these:

Volkswagen RC510:

This is my car’s head unit, as seen in some VW cars. I started looking at this before VW’s Diesel scandal, but while this looks like a cool challenge, there are some logistical concerns: I use the car everyday and can’t afford to “crash” it. Car hacking is a booming field though, might be something I’ll return to later.

A-Rival Spoq SQ-100

This is a GPS sportswatch more suited for trail running. It is actually easier to hack than the TomTom, because the firmware is not encrypted. But the watch didn’t interest me much because it’s based on an AVR architecture (as opposed to ARM), doesn’t have Bluetooth, and isn’t very popular. Might come back to it later, though.

This is a GPS sportswatch more suited for trail running. It is actually easier to hack than the TomTom, because the firmware is not encrypted. But the watch didn’t interest me much because it’s based on an AVR architecture (as opposed to ARM), doesn’t have Bluetooth, and isn’t very popular. Might come back to it later, though.

The TomTom Runner

The Tomtom runner is a cooler watch. If you’re looking for a good and cheap GPS running watch this is it. It has Bluetooth low-energy, an ARM processor, and TomTom is really getting into the market that’s mostly dominated by Garmin now, so let’s keep investigating.

The first thing I did was to download the firmware for all these devices. Firmware for these devices can usually be found on the manufacturer’s web site, user forums etc.

Analyzing the firmware files for these devices was done using binwalk. The results were discouraging: Out of the three devices, the main firmware was encrypted using a 16 byte block cipher (probably AES) in two of them. It appears that most of the firmware these days is distributed encrypted.

04. Attack Surface

I chose the TomTom, so the next thing to do was to look at it from a hacker’s perspective. I’m good at breaking things but not so good at putting them back together, and since I use the watch regularly for its intended purpose, I made a promise to myself not to try to open it and attempt any sort of hardware hacking via JTAG/Debug pins. Also there would likely be at least some protections and it’s a steep learning curve with some penalty for error.

So what are our options from an external perspective? I figured these were the attack vectors:

- User Interface: You can use the four-way D-Pad to try and attack the device. I tried, and failed.

- GPS: If you have a HackRF or similar you could possibly attack the device via its GPS receiver, but I really don’t see the point of it :)

- Bluetooth: The device has a bluetooth interface that works similarly to USB at the protocol level. From what I read it is possible to interface with in a way similar to USB as long as the device is paired. This could be done using ttblue.

- USB Interface: This was the preferred attack method. More on this later.

05. Firmware

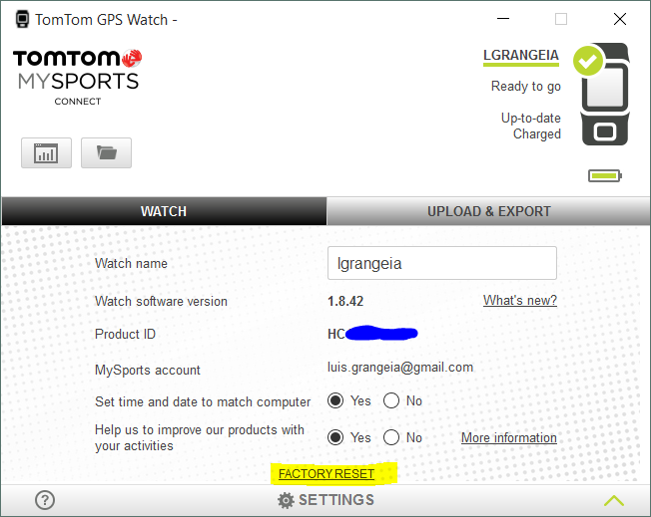

So step one of hacking any device is trying to get to its software. I did that by looking at how the official TomTom software updates the watch’s Firmware:

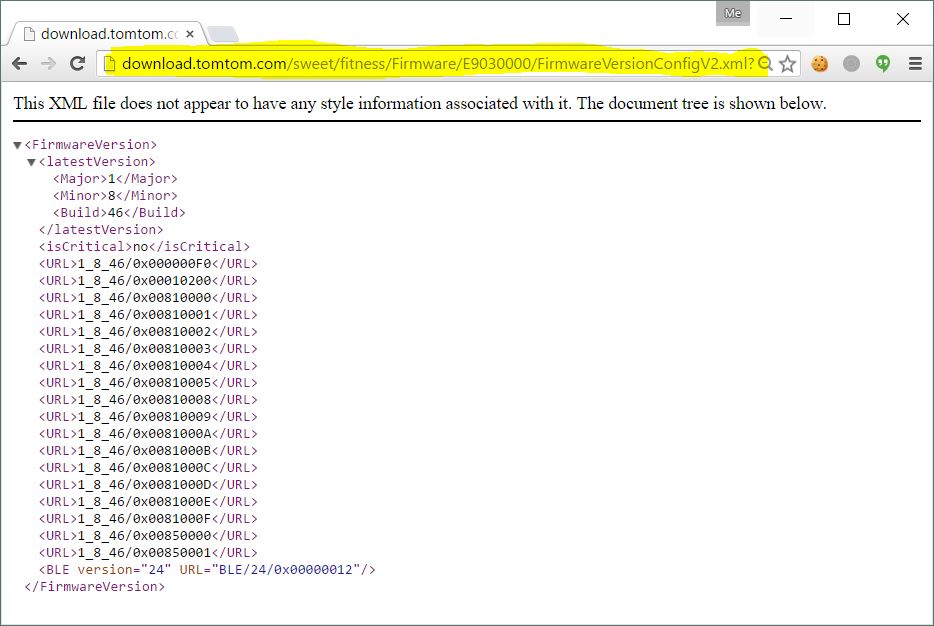

Using Wireshark and forcing an update one can find the location of the firmware files:

For the observant: yes, this is a regular HTTP page, no SSL. Remember this later.

There are lots of files here, the ones that matter to us are:

- 0x000000F0 is the main Firmware file;

- 0x0081000* are language resource files (eng / ger / por / etc.)

There were other files: device configuration files, firmware for the GPS and BLE modules. These last two are unencrypted but were not very interesting.

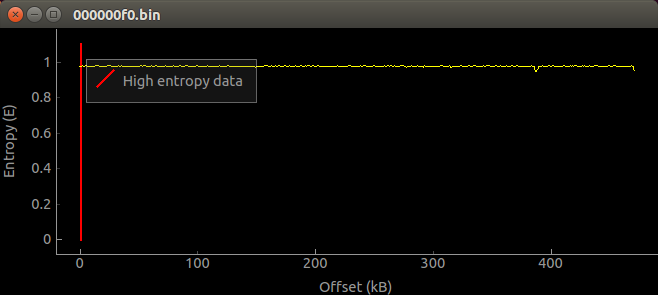

The larger file (around ~400kb) is 0x000000F0 and looks like the main firmware. Looking at it with binwalk gave us this:

$ binwalk -BEH 0x000000F0

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL HEURISTIC ENTROPY ANALYSIS

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1024 0x400 High entropy data, best guess: encrypted, size: 470544, 0 low entropy blocks

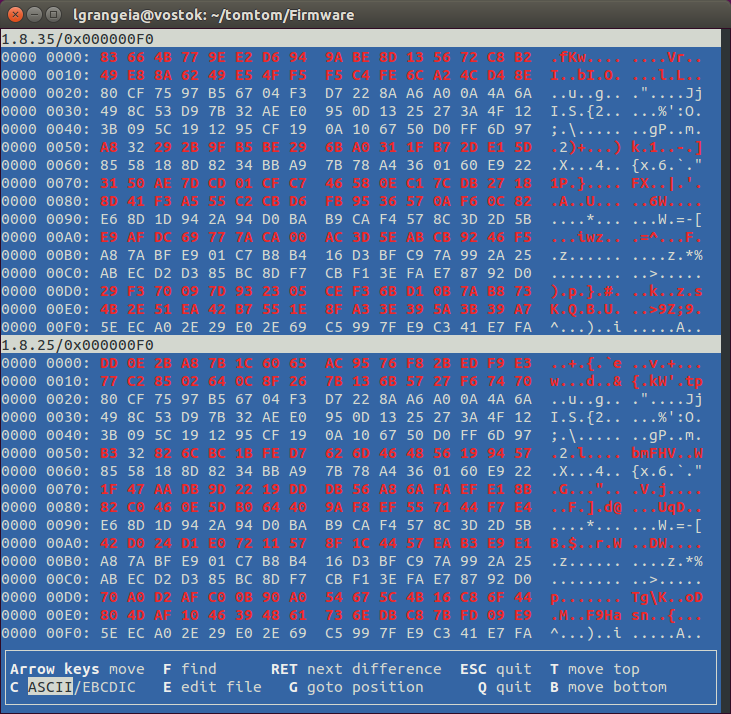

Want further proof that this is encrypted? Check out this comparison of two different firmware versions, using vbindiff:

Note that:

- Files are different in 16 byte blocks

- There are blocks that are the equal interleaved with blocks that are different

This means it’s very likely that this is some sort of block cipher in ECB Mode. The most common 16-byte block cipher, by far, is (you guessed it) AES.

Lets take a step back for now regarding firmware analysis. Let’s look at what we can learn about the device’s hardware.

06. Hardware

What can we learn about the watch hardware without opening it? This is probably old news to veteran reverse engineers, but here goes: pretty much any RF emitting device sold in the United States is tested by the FCC, that eventually publishes its report containing all sorts of juicy information and photos.

There’s a nice search engine for FCC report data (the official site seems purposefully obtuse) by Dominic Spill, you just need the FCC ID (S4L8RS00 in our case). Here is the obligatory full frontal nude photo of our device, courtesy of the FCC:

The big black chips are:

- Micron N25Q032A13ESC40F: This is a serial EEPROM with 4MB capacity. It’s the “hard-drive” of the device, where the exercise files are stored, among other things.

- Texas Instruments CC2541: This is the Bluetooth chip.

- Atmel ATSAM4S8C: Micro-Controller Unit (MCU). This is the “brain” of the device, and contains: - A Cortex-M4 ARM core - 512 kb of Flash memory the firmware and bootloader reside - 128 kb of RAM memory

The GPS chip is soldered on a daughterboard near the D-PAD.

This information will be useful later on. Since now we have a good enough picture of the device’s innards, let’s move on.

A sidenote, that PDF Datasheet of the Atmel I linked up there was my bedside reading for a long time. In my foray as an hardware reverse engineer you really should embrace the datasheet. And this one’s pretty thorough, which was a nice experience. Hooray for Atmel :)

06. USB Communications

I had some work cut out for me in this field. There’s already a nice piece of open source software that does most things the official TomTom Windows software does. You can check it out here: ttwatch.

I looked at the source which is very easy to read. If you compile it with ./configure --with-unsafe you’ll get a few additional nifty command line options. Turns out that a lot of the USB communication with the watch is simply read / write commands to its internal EEPROM.

I did some more investigations regarding USB, and made a crude fork of ttwatch that removes some sanity checks and implements a new tool, ttdiag to send/receive raw packets from/to the device. I also used USBPcap on Windows to record the communication between the device and the TomTom MySports Connect software.

These investigations led me to find a lot of interesting and undocumented USB commands for the device. The USB communication is quite simple, with each command composed by at least the following four bytes:

09 02 01 0E

"09" -> Indicates a command to the watch (preamble)

"02" -> Size of message

"01" -> sequence number. Should increment after each command.

"0E" -> Actual command byte (this one formats the EEPROM)

Some commands have arguments, such as file contents, etc. Since each command is a single byte, it was easy to cycle through all possible commands. The full list is available here. There were some interesting commands, such as a hidden test menu, a command that took “screenshots” of the device and saved them on the EEPROM, etc. Here is the test menu testing the accelerometer sensor:

Most of the commands to/from the watch involve reading / writing to the 4MB EEPROM we saw earlier. ttwatch already does that for us. We can read, write and list files:

root@kali:~/usb# ttwatch -l

0x00000030: 16072

0x00810004: 4198

0x00810005: 4136

0x00810009: 3968

0x0081000b: 3980

0x0081000a: 4152

0x0081000e: 3957

0x0081000f: 4156

0x0081000c: 4003

0x00810002: 4115

[...]

root@kali:~/usb# ttwatch -r 0x00f20000

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<preferences version="1" modified="seg set 21 13:34:28 2015">

<ephemerisModified>0</ephemerisModified>

<SyncTimeToPC>1</SyncTimeToPC>

<SendAnonymousData>1</SendAnonymousData>

<WatchWindowMinimized>0</WatchWindowMinimized>

<watchName>lgrangeia</watchName>

<ConfigURL>https://mysports.tomtom.com/service/config/config.json</ConfigURL>

<exporters>

</exporters>

</preferences>

Turns out that if you write the firmware file you saw earlier from download.tomtom.com, the next time you unplug the watch from USB it will reboot and reflash the file, assuming it is a valid firmware file.

07. To be continued…

This is turning up to be a long post so I won’t keep you longer for today. I will keep my promise and show you how I exploited this watch and extracted / modified its firmware. Next post will be about finding that memory corruption bug and controlling execution.